- Tumblr

We catch up with the Ghanaian artist on his latest project that recreates the iconic 'A Great Day In Harlem' photo—but with a colorful twist.

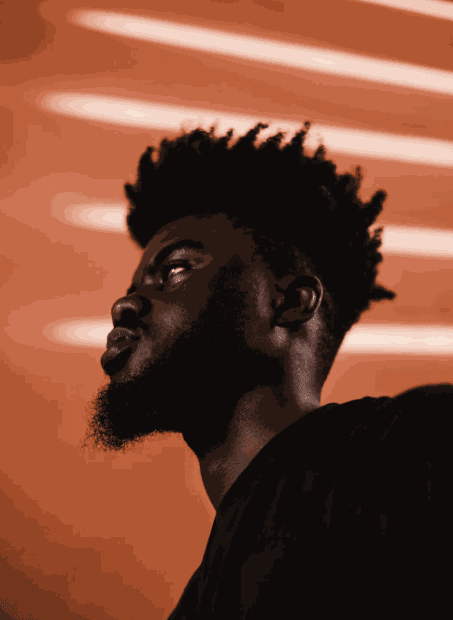

If you've come across Prince Gyasi's work on Instagram, you'll know his conceptual images depicting daily life and featuring beautiful faces in Ghana are full of striking, bright colors. His latest project for Apple doesn't fall short of this unforgettable aesthetic.

The Ghanaian photographer cast a wide net to gather the young and old greats of hiplife—a genre birthed in his home country that fuses hip hop, highlife and Ghana's diverse languages—for A Great Day In Accra. In this photo series, Gyasi simply wanted to give hiplife culture and the torchbearers of the sound their long overdue props.

The series was shot on location at Independence Square, where Martin Luther King Jr. watched Kwame Nkrumah declare Ghana's independence in 1957. "By reuniting and photographing both old and new hiplife artists, I'm letting the rest of the world know about the genre's impact in Ghana and beyond," Gyasi said in a statement about A Great Day In Accra. "People need to hear about the culture, the source of our rhythm, our music, what influences our arts. It's our history from our perspective. I want to make sure the new generation doesn't lose their identity or forget about the pioneers who paved the way for them to lift their own voices."

The series was also paired with a mini-doc, directed by Joshua Kissi, featuring Reggie Rockstone, Okyeame Kwame, Abrewa Nana—Ghana's first female hiplife artist, Joey B, E.L and more.

We caught up with Prince Gyasi to learn more about A Great Day In Accra. Take a look at our conversation below.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Antoinette Isama for OkayAfrica: What sparked the idea to make a multigenerational moment featuring the greats of hiplife in one image?

Prince Gyasi: I came up with this idea because I felt that hiplife culture isn't represented that much. Highlife music was the basis of what we're hearing. And hiplife music was an attempt for Ghanaians to accept to hip hop culture in Ghana. There was an artist called Reggie Rockstone who came to Ghana from London and he decided to do rap music in his own language—he had an American influence. What he did years ago is what we're hearing now from these new artists in Nigeria, or in Ghana, or these artists that are doing afrotrap which is related to hip hop too. I felt like as an artist I had to let people know the culture through my art. That's the only way that people can be able to relate to the music from Ghana. And I felt that hiplife is not out there that much—it's all afrobeats. I want people to know that rap music in Ghana, and I wanted the young ones to not forget about a where they come from and where the music they hear today started from. These artists paved the way for them to still raise our own voices. I also was inspired by "A Great Day In Harlem," which was shot in 1958 by Art Kane featuring the great jazz artists of that time. I made an attempt to recreate that image in Accra which features all hiplife artists of old and new in one iconic photo.

After watching the video clip on Apple's IGTV, I got a sense that there was a creative synergy between you and Joshua Kissi behind the scenes. What was it like working with him—another artist from the Ghanaian diaspora?

It was great. It was good seeing him do video because we always see his still images. It was a great experience capturing the city, capturing these icons. And the video came out good, so I'm excited.

Was there a particular look or theme you were going for—in terms of the aesthetic of the images you captured—that you wanted to keep in mind while taking photos with the artists?

There's a slight difference between the photographer and a visual artist. A visual artist, like myself, is someone who creates a concept piece. And a photographer is actually a job where you are capturing a moment. Even though I got to capture the moment, which was my first time because I usually do conceptual storytelling, I had to make it look like it was a piece that I already had in mind. The theme was to show a colorful capsule of these artists and their personalities. It's just about enlightening people—even though we're talking about hiplife—that hiplife was colorful. Colors also come with a lot of symbolic meaning. Ghana's also a colorful city, so we had to show that through those photos so people know the difference between each artist.

Even though you consider yourself to be a visual artist, do you still feel the need to have a sense of responsibility to be a documentarian of the culture in a way?

Yes. With the art pieces that I've presented in Seattle, Texas and Art Basel Miami, they're basically a authentic representation on the culture, how it looks like, the truth of what is happening here? Most people know I have a series called Boxed Kids, which tells the story of my organization with the same name. Jamestown is one of the oldest districts in Accra and it's a fishing city which has a generational cycle that goes round and round and never changes because these kids come to life and grow up to be fishermen. My partner and I decided to come up with this organization to stop the practice of putting kids through fishing while they have to be in school.

We saw a kid making a mini-boat from sticks. We thought that was creative, but the kid doesn't know what he was doing—they were not educated. So we wanted to put more life in that. As a visual artist, I have to tell my story the same way because Kwame Nkrumah said, "The new African Renaissance has to tell their story as it is." This is what I'm doing. This is what I'm supposed to do—this what every African is supposed to do. We're supposed to tell our story as it is and not wait for anybody to come tell it for us because nobody else can tell our stories. We can. So I think it's important that I always show the culture through that. Showing a kid who is hopeful for the future and let them know that they will be someone bigger in the future. These are the stories we have to tell people—but not show them in a negative way, but still show them in a colorful way, in a beautiful way, so people don't see Africa as a negative space.